My uncle, like my grandmother, went by a few different names—Lee for the guys he grew up with in Harlem, Mr. Lee with his family in Virginia, and Nookie, strictly for family. If you ever jokingly called him Nookie, trying to imitate one of his relatives who have mostly passed on, you could count on meeting his wrath, followed by, “THAT’S FOR FAMILY ONLY!” My cousin Jr. got to call him Dad, but for me, he was a surrogate father in my own dad’s absence.

He was the coolest guy during every decade of my life. He was the man on the block that everyone greeted, and the one that even the guys doing the wrong thing left alone, because he was a sincere OG who naturally commanded respect.

He was also my protector. I remember when I was a kid, and my grandmother was being too harsh, saying hurtful things to me. After her insults, the walls would vibrate from him shouting on my behalf. I can still close my eyes and hear his voice, like Samuel L. Jackson, yelling, “Don’t tell her that, Shug! Stop saying that to that girl. Stop—leave her alone, Rose.”

He was always great with kids, and everyone envied me because he was my uncle. I remember him taking me to the playground at Morningside Park, and he would help all the kids down the slide, not just me. When I got older, I remember him telling the older kids in front of the house, prone to bullying, that I was his niece, and they better leave me alone. He felt bad for me when I had to go to summer school, not because I needed it, but because my grandmother just wanted to keep me busy. Going to summer school when it’s not required is torture, not camp. From that summer on, he introduced me to everyone we met as his “favorite niece, EVETTE,” with the same passion he’d use when defending me to my grandma.

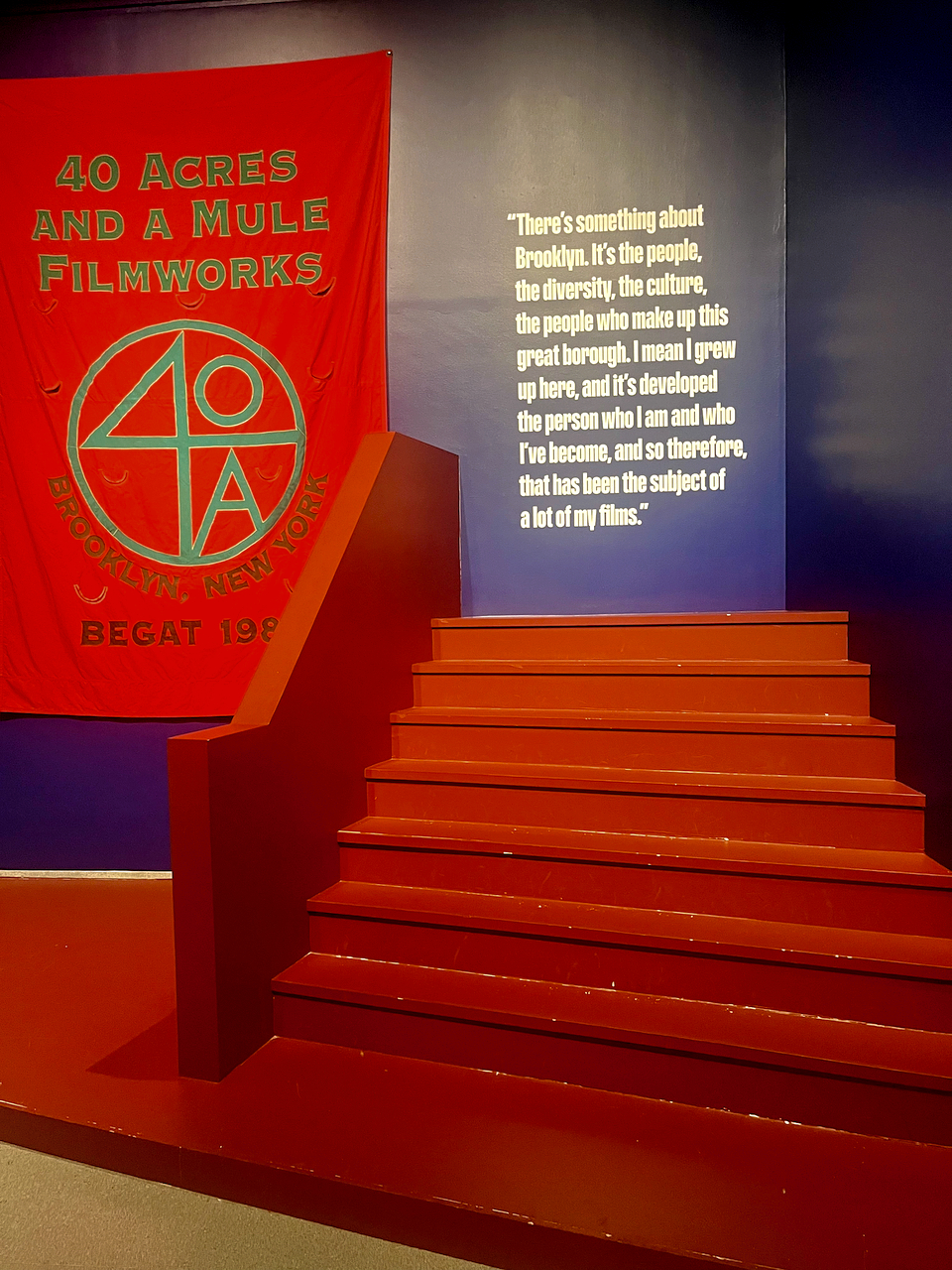

Other summers, he’d take me to the pool at Marcus Garvey Park. He made sure I got to explore the neighborhood safely, beyond the stoop. I’d wait every day until about 11 am for Nookie to arrive so I could escape my grandmother. The first time I went to the Apollo Theater wasn’t on a school field trip like most kids. My uncle took me after casually running into The Sandman at the park, and we got a tour of the stage with him. I even got to rub the tree stump, just like the amateur performers do before stepping out in front of the crowd.

He made sure I could enjoy being a kid. He was the only one who would buy us McDonald’s and make sure we ordered for ourselves. I went from ordering a Happy Meal to confidently asking for a “Number 2 with no pickles.” He’d also stand up for me when my grandma wouldn’t let me get Mr. Softee when the truck came late at night. “She wants the one from the truck,” he’d say, and each time I ran out to meet it, I’d stop at his door for the dollar he had ready—just enough for a vanilla cone with sprinkles.

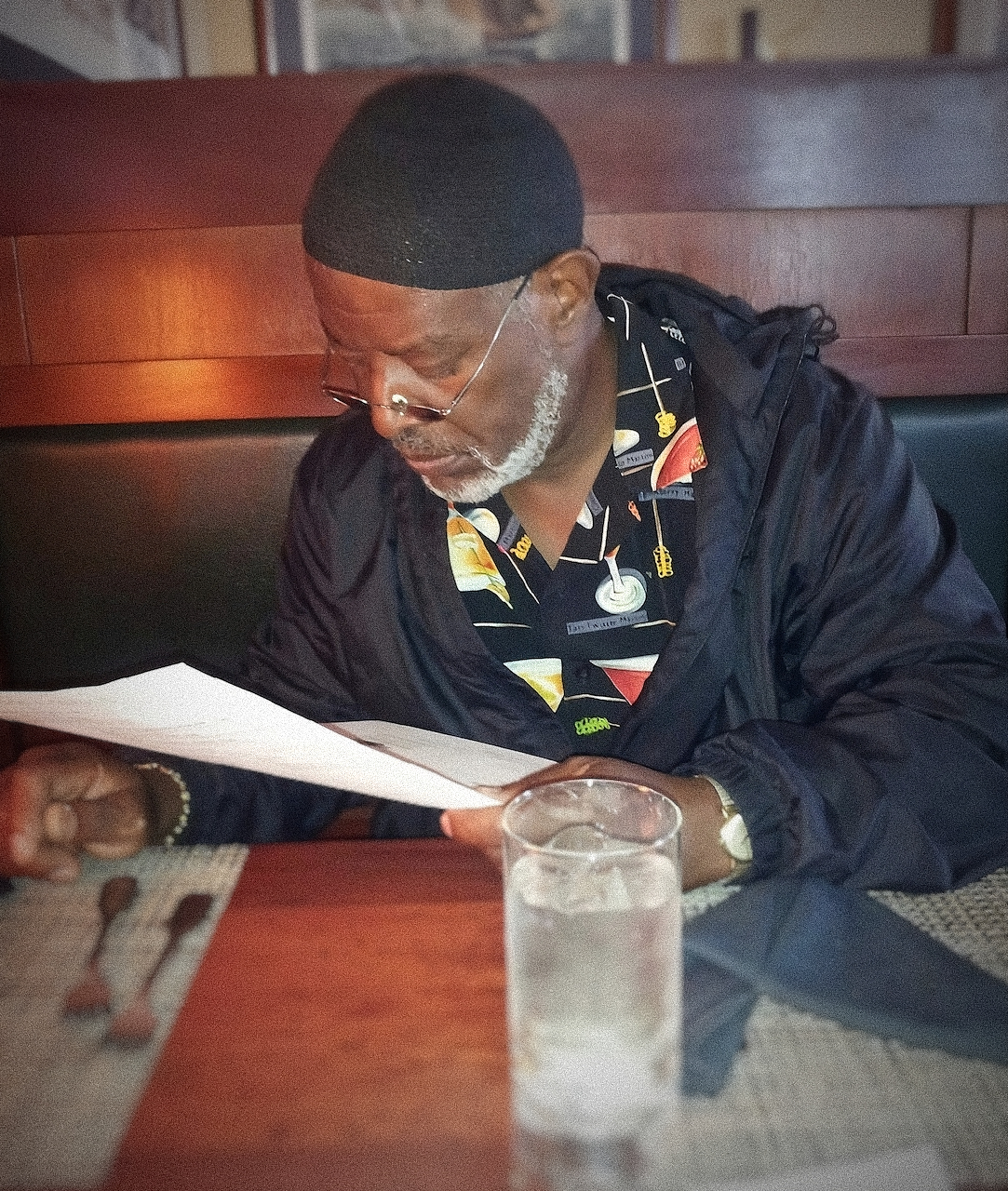

Later, when I visited Virginia—once with my mom and a few times when my best friend briefly moved there—he’d take me to Cracker Barrel, and we’d catch up. During our last visit, years before he got sick again and stopped treatment, I saw his weight loss and noticed how he was pretending to have an appetite, though chemo made him too ill to eat. “Don’t look so sad,” he told me in his smooth voice. His catchphrases—“naturally,” “very good,” “it’s cool,” and “alright, baby”—always linger in my memory, so does the little song he’d sing to himself when passing time: “lullaby, lullaby, gypsy.”

He passed right before Christmas, just before the pandemic in 2018. Watching him fearlessly accept his fate, while I was with him in Virginia during his final days, was the bravest thing I’ve ever seen. He was a realist and knew it was his last Thanksgiving. I’m glad I followed my instincts and went down to see him before Christmas, despite him trying to keep me from coming because he didn’t want to upset me with how bad things had gotten.

The three weeks I spent with him were heartbreaking —going from watching him become weaker at home, to visiting him in the hospital every day, to helping his longtime partner choose a casket, and finally creating a slideshow for his funeral. My uncle was private and didn’t like false admiration. He only really liked a handful of people, though he knew everyone. The service was small, just immediate family and a few close friends. I eulogized him for my mom and Uncle Herbert, who were present, and for our family in South Carolina, where he spent his summers growing up. There were very few usable photos for the slideshow because he hardly ever took pictures. But whether you met him in the ’70s, ’80s, ’90s, or before he passed, he always looked the same—tinted aviators, a gold chain, a few gold teeth in his famous smile, silk printed shirts he called his blouses, and, later in life, a Kufi. He had eyes just like my grandfather’s, my mother’s, and mine. He also favored my mother the most. I don’t have a single picture of the two of us, but I have memories and landmarks that remind me of him.

My family has never been good with grieving. My mom once found out her favorite uncle had passed months after the fact because my grandmother didn’t want to upset her during a difficult pregnancy. I was determined not to let anyone do that to me about my favorite uncle, so I made sure he always told me the truth about his condition, which is why I showed up for him at the end.

Leroy Massey taught me how to advocate for myself and to always try to do the right thing. During his final days, when people tend to tell the truth, say their goodbyes, and leave you with advice, he told me simply, “Just keep doing right, Evette, and don’t worry so much. Slow down, don’t get too excited—you’ll be alright.” He should have lived well into his 90s. His loss hurt the most.

I hum his signature tune in my head every now and then, and when I do, I feel joy and laugh to myself.

I pay homage to him and I design and create from the references he introduced me to during our explorations around the neighborhood when I was a kid.